Source: African Development Bank

Nutrition Crisis in Nigeria

A malnutrition epidemic is looming over Nigeria, fueled by a cost-of-living crisis, sub-optimised primary healthcare systems, and startling levels of insecurity, according to health professionals. Close to 32 million Nigerians, or around 15% of the population, are hungry due to a situation that was made more severe by macro-economic reforms. Food costs skyrocketed, driving inflation to a near 30-year high, and real incomes have lagged far behind.

Aid agencies, have reported the most worrying rises in malnutrition in Nigeria’s rural north, where poverty is more deeply rooted. The International Committee of the Red Cross has noted an increase in the number of seriously malnourished children being admitted to the health facilities it serves in Nigeria’s northeast. In addition, a medical organisation, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), conducted a mass screening in June 2024 and discovered that one in four children under five in the Shinkafi and Zurmi regions of northwest Zamfara state was severely malnourished. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declares an emergency when the rate of malnutrition reaches 15%.

A shortage of ready-to-use therapeutic food, which is intended to save the lives of fragile newborns, has made the nutrition crisis worse as UNICEF, the UN agency for children, faces a financial constraint that affects all of West Africa. Ready-to-eat (RTE) nutrition packs—such as RUTFs (Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Foods) and meal replacement bars or emergency rations are pre-packaged, shelf-stable, nutrient-dense meals designed for malnourished children, emergency and conflict zones, disaster relief efforts, and field operations for humanitarian workers or soldiers. Examples of RTE nutrition packs include Plumpy’Nut, which requires no cooking, water, or refrigeration, making it a lifesaving tool in crises.

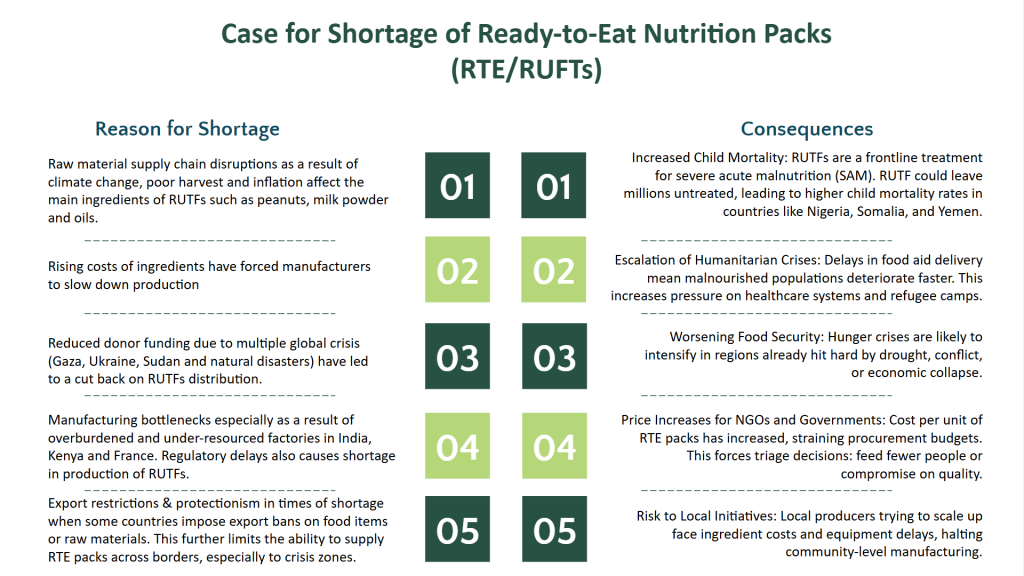

Figure 1: Causes of and implications of shortage of Ready-to-Eat (RtE) nutrition packs.

Current State of Nutrition Financing in Nigeria

At the 2021 N4G Tokyo Summit, Nigeria pledged to increase domestic funding for nutrition programs and strengthen accountability mechanisms. However, progress has been slow. To combat malnutrition, there is a need for increased budgetary allocations, implementation of financial realistic plans, and tracking of disbursements at the federal and state levels. In this section, we’ll explore the policies and initiatives stakeholders and partners have made towards nutrition in recent years.

Figure 2: Nutrition Financing Policies and Initiatives

Some factors limit Nutrition Financing in Nigeria

Despite efforts and international commitments, Nigeria still struggles to fund nutrition programs consistently. These challenges don’t just exist on paper; they show up in missed targets and children who go hungry when they shouldn’t. Here are some key challenges:

- Low and Inconsistent Budget Allocations

Most nutrition programs in Nigeria depend heavily on donor funding, with government budgets often falling short. While the country has made several high-level commitments, like signing onto the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement and launching the National Multi-Sectoral Plan of Action for Nutrition, the actual money committed is far below what’s needed. In the 2024 Federal Ministry of Health budget, 1.47%, amounting to 18 billion Naira, was allocated to nutrition initiatives and programmes. Conversely, OECD countries allocate approximately 8.4% of their total health budgets to address the consequences of unhealthy weight, encompassing diet-related diseases and obesity-related healthcare costs. In comparison. Nigeria’s commitment to nutrition initiatives is still far off from an acceptable level.

- Fragmentation Across Sectors and Levels of Government

Nutrition touches many sectors, such as health, agriculture, education, water, and environment, but there’s often poor coordination between ministries and agencies. Responsibilities overlap, and communication gaps are common. For example, the Ministry of Health may fund community nutrition education, while the Ministry of Agriculture focuses on food security, and the Ministry of Education runs school meal programs. But these efforts rarely align. At the sub-national level, nutrition often gets lost in bureaucracy, with no clear lead agency or accountability.

- Weak Data and Monitoring Systems

Good policy needs good data. Unfortunately, Nigeria still faces gaps in nutrition data collection, especially at the local level. For example, some states lack updated figures on child malnutrition, stunting, or anaemia. While in other states, budget tracking is a major issue, making it hard to know how much is spent on nutrition each year. A data strategy should be a part of the national nutrition strategy highlighted below, as tracking progress, course-correcting, and agility are critical components of a national strategy. These can only be achieved with high-quality data systems.

- Over-Reliance on Donors

Nigeria has benefited from support from development partners like UNICEF, the World Bank, USAID, and the Gates Foundation. While this has helped launch many programs, it has also led to overdependence on external funding. This can lead to problems such as government actors becoming less motivated to take responsibility, and in a situation where donors shift priorities or, as in the case of the recent USAID freeze, many programs will collapse. Countries like Ethiopia and Peru built successful national nutrition programs by combining donor support with strong domestic financing and ownership. There is a need to provide dual-purpose economic and social impact cases for nutrition investments to catalyse private sector funding.

- Political Will and Long-Term Vision

Nutrition is often seen as a “soft issue” because it’s not as urgent as infrastructure, security, or economic reform. As a result, it doesn’t always get the attention it deserves from policy-makers. There’s also a lack of long-term planning, with many nutrition policies or interventions lasting only as long as a particular administration or donor project.

There is a strong Economic case for Investing in Nutrition

Investing in nutrition is vital for public health and makes strong economic sense for Nigeria. The country faces significant financial losses due to malnutrition, and experiences from other countries demonstrate that targeted nutritional investments can yield substantial economic benefits. Nutrition (actually the lack of it) imposes a heavy economic burden on Nigeria. Recent analyses reveal that undernutrition costs the nation approximately $56 billion annually, about 12.2% of its Gross National Income (GNI). This staggering figure encompasses losses from reduced productivity, increased healthcare expenses, and lost educational outcomes.

Furthermore, Vice President Kashim Shettima highlighted that Nigeria loses around $2.5 billion each year due to a 33% prevalence of chronic malnutrition. This situation leads to higher child mortality rates and a decreased likelihood of children reaching older ages, thereby affecting the nation’s workforce and economic potential.

Lessons from Peru

Other countries have successfully addressed malnutrition, resulting in notable economic improvements:

Figure 3: How Peru Achieved Reduction in Stunting

For Nigeria, prioritising nutrition investments can lead to similar positive outcomes. By allocating resources to effective nutrition programs, the country can expect a healthier population, improved educational performance, and a more productive workforce. These changes are essential for breaking the cycle of poverty and fostering sustainable economic development. To put it in perspective, addressing malnutrition is not just a health imperative but an economic necessity for Nigeria. The substantial financial losses attributed to malnutrition highlight the urgent need for increased investment in nutrition. Learning from countries like Peru and Bangladesh, Nigeria can implement effective strategies to enhance nutrition, thereby securing a healthier and more prosperous future for its citizens.

Policy Action can catalyse Nutrition Investments in Nigeria

Source: This is Africa

Tackling malnutrition in Nigeria is possible—but only if take bold, targeted policy actions now. Here are key strategies the government and its partners can use to unlock more funding and improve nutrition outcomes across the country:

- Increase Government Budget for Nutrition

The most obvious policy action is to provide more budgetary allocation to nutrition programs. In 2024 nutrition got 1.46% of the total health budget allocation, a figure that is far below what’s needed. Comparatively, The federal and state governments should allocate a dedicated portion of their health, education, and agriculture budgets specifically to nutrition. For example, countries like Ethiopia and Senegal have created line items in their national budgets for nutrition, making it easier to track and increase funding. In Nigeria, having a clear and separate line for nutrition in the budget would make sure the money doesn’t get lost in the system.

- Strengthen Multi-Sector Collaboration

Nutrition isn’t just the health ministry’s job. It connects to agriculture (food supply), education (school feeding), water and sanitation (clean environments), and social welfare. But often, these ministries work in silos. To fix this, the Nigerian government should employ the ‘mission-centred’ approach to policy and innovation by forming stronger inter-ministerial collaboration on nutrition and creating joint action plans that pool resources and expertise from all relevant sectors. This “mission-centred” approach has worked in Peru, where strong leadership and cross-sector teamwork significantly reduced child stunting rates in less than a decade.

The government doesn’t have to go it alone. The private sector also a huge role to play in solving the nutrition crisis. For example, food companies can fortify products with essential vitamins and minerals. Banks and telecoms can support mobile money nutrition vouchers or nutrition messaging platforms. Local agribusinesses can help improve food supply chains and reduce food loss.

To support these partnerships, the Nigerian government can offer fiscal or other incentives to companies that invest in nutrition and create nutrition investment platforms that match private funding with public goals.

- Explore Innovative Financing Options

To bridge the funding gap, Nigeria should look beyond traditional sources. Innovative tools can unlock new money for nutrition programs. Some ideas include government-backed nutrition bonds, the proceeds of which go directly to nutrition-focused programs. Another way is through results-based financing, where donors or development partners provide funds only after programs show real, measurable results. Rwanda has used performance-based financing in the health sector with great success and Nigeria can adopt similar models for nutrition.

- Improve Transparency and Accountability

More funding is only adequate if it’s used well. One of the most significant barriers to progress is the lack of transparency in how nutrition funds are allocated and spent. To build trust and efficiency, Nigerian stakeholders should employ digital tracking systems to monitor nutrition spending, publish nutrition budget reports regularly at both national and state levels, and involve civil society and community-based organisations in monitoring and reporting on program delivery. This level of transparency helps ensure that money reaches the communities that need it most and that policymakers stay accountable for results.

- Build Political Will through Advocacy and Public Engagement

None of these strategies work without strong political support. Advocacy groups, health professionals, and the public must continue to push leaders to act. Advocacy groups can organise high-level public-private dialogues and engage the media and influencers to discuss malnutrition as a national emergency. There is also a need to mobilise community voices and champions, especially mothers, teachers, and grassroot leaders, to keep the pressure on. When nutrition becomes a political priority, it receives the attention and resources it deserves.

Conclusion

Source: CIAT/NeilPalmer

From the foregoing, malnutrition isn’t just a statistic; it’s a daily reality for millions of Nigerians. It keeps children from growing, learning, and thriving. It holds back communities. And it quietly drains billions from our economy each year. The numbers are stark, the stakes are high, but the path forward is clear.

Nigeria stands at a critical turning point. The country can choose to stay reactive treating malnutrition as an afterthought or it can rise to the challenge and take bold, coordinated actions. There is real momentum building. On the horizon is the revision of the National Policy on Food and Nutrition, with a strong focus on multi-sectoral budgeting, improved coordination at federal and state levels, and mandatory nutrition reporting and accountability. This updated policy is expected to be finalised and rolled out in late 2025, bringing clearer frameworks for financing and implementation. Nigeria is also expected to play a key role at upcoming global nutrition events, including the African Union Year of Nutrition follow-up (2025), the 2025 Global Nutrition Summit (Tokyo, Japan), and the UN Decade of Action on Nutrition (2016–2025) which provides a strong push for governments, including Nigeria, to accelerate impact.

If the country takes advantage of these opportunities, a child born in the country’s rural North in 2025 will potentially have access to fortified foods, clean water, and a school with a high quality and regular feeding programmes. In addition, her mother no longer travels five hours to a clinic because local health workers are trained in nutrition. More importantly, her government sees her not as a burden but as an investment. According to projections by the World Bank and the African Union, if Nigeria scales up nutrition investments today, it could save nearly 2 million lives and add $29 billion to the economy by 2030.

This crisis is too big an opportunity to waste.